This morning, a Department of Energy helicopter buzzed above cities and suburbs in eastern Massachusetts, scanning for radiation in advance of the 125th Boston Marathon. The sweep is part of security preparations to help first responders pinpoint possible “dirty bombs” and other terrorist activities before they claim any lives.

The flight started with a thorough scan of the starting line in the western suburb of Hopkinton before flying along the 26.2-mile route to the finish line in Boston, where the helicopter performed another comprehensive survey. The craft flew at low altitude the entire time, dipping below 100 feet on several occasions, according to FlightAware.

FlightAware

The twin-engine Bell 412 (tail number N412DE) is operated by the National Nuclear Security Administration, a division of the Department of Energy that is responsible for everything from nonproliferation to maintaining the nation’s nuclear stockpile. The helicopter is part of the agency’s Aerial Measuring System, which routinely performs radiological surveys before major events, including presidential inaugurations, Super Bowls, and New Year’s Eve celebrations in Las Vegas.

The NNSA will fly additional surveys in the Boston area over the next three days, including Monday, when the marathon will be run. Today’s flight is intended to develop a map of background radiation sources, which will help the helicopter and other ground-based sensors detect any unusual radiological activity on race day, including so-called “dirty bombs” that use traditional explosives to scatter radioactive material.

Mapping the sources

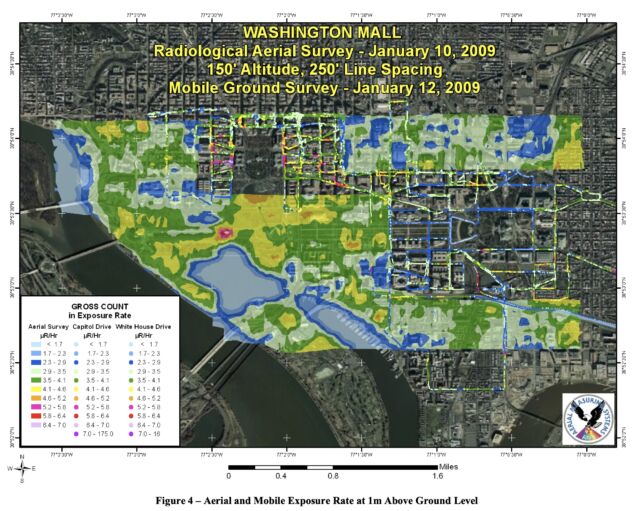

Background radiation maps are critical in these situations because the earth is constantly emitting varying levels of radiation. Some types of rocks emit more than others, and when they’re near or on the earth’s surface, they can cause spikes that might otherwise set off detectors and distract first responders. The National World War II Memorial in Washington, DC, for example, is made from large amounts of granite and emits enough radiation to merit a special mention in the radiation survey report for the 2009 presidential inauguration.

US Department of Energy

Onboard the AMS helicopter, two pilots fly the craft while a mission scientist and equipment operator monitor the sensors and computers from the back. Fully loaded, the helicopter can fly for about two and a half hours before needing to refuel. Two pods that hang off the sides house four sodium iodide sensor modules that record gamma radiation once every second. The helicopter can also fly with helium-3 sensors used to detect neutron radiation.

The entire AMS fleet consists of two Bell 412 helicopters and three Beechcraft BN-350 airplanes split between Joint Base Andrews in Maryland and Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada.

The Boston Marathon has become a high-security event ever since two domestic terrorists detonated homemade pressure-cooker bombs at the finish line in 2013, killing three and injuring more than 250. The attack sparked a days-long manhunt that culminated in a shootout in nearby Watertown. While the AMS surveys probably can’t detect the types of explosives used in the 2013 bombing, the surveys are part of a larger effort to secure the event. The commonwealth has designated the route as a “no drone zone,” and police are stationed along the entire length of the race. Checkpoints are scattered throughout high-traffic areas where officers can search bags and coolers for weapons or explosives.

It may seem like a lot of security for one race, but few people in the Boston area complain. I passed through the finish line area less than an hour before the 2013 bombing, and I holed up during the subsequent days-long lockdown. I still attend the race to cheer the runners, and every year, I’m happy to see federal and state law enforcement preparing for a range of possible incidents, no matter how remote they may seem.