When the James Webb Space Telescope launched late last year, astronomers bestowed it with an infinite number of missions. I say infinite because the ultimate goal of this engineering marvel isn’t merely to answer every question we have about the universe. It’s to answer questions no mortal human would’ve thought to ask.

But before skipping to that mind-bending end goal, our brilliant new lens is dutifully strutting through the tasks we did give it, one of which is to pierce through veils of cosmic gas and dust and reveal secret star escapades within. Things standard optical telescopes, like Hubble, can’t always see.

Behold, on Tuesday, the JWST decoded a glimmering scene behind one of space’s dark curtains, a dusty canopy that enshrouds a pair of merging galaxies some 270 million light-years away from Earth.

The JWST caught a glimpse of a sparkly, sparkly cosmic scene.

ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, L. Armus, A. Evans

What am I looking at?

We have two realms, dubbed IC 1623 A and B, stuck on a collision course through space and time. They’re located in the constellation Cetus, and have long been of interest to scientists for a few reasons.

Perhaps most strikingly, they might be in the process of forming a supermassive black hole — a gargantuan void with enough gravitational force to warp the fabric of our universe as we know it.

But that budding cavern of destruction is expected to be strung with a necklace of light.

The ultra-high intensity of galaxy merger IC 1623 also spurred the creation of a zippy star-forming region nearby. It’s called a starburst, and this one in particular, according to the European Space Agency, is creating new stars at a rate more than 20 times that of the Milky Way galaxy.

And this is what the JWST caught.

Hubble already gave us a preliminary view of IC 1623 A and B, but astronomy’s newest contract with space has pierced through the duo’s cosmic veil, just as scientists hoped it would since the beginning. By doing so, it’s shown us the luminous core of this merger and presented humanity with a full, mesmerizing image of IC 1623 rather than a concealed one with a central region left to our imagination.

Here’s Hubble’s view of merging galaxies IC 1623 A and B. It’s much less sparkly, because the central regions of these realms are obscured by dark dust.

ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, L. Armus, A. Evans

Why can the JWST do what Hubble can’t?

Two words: infrared imaging.

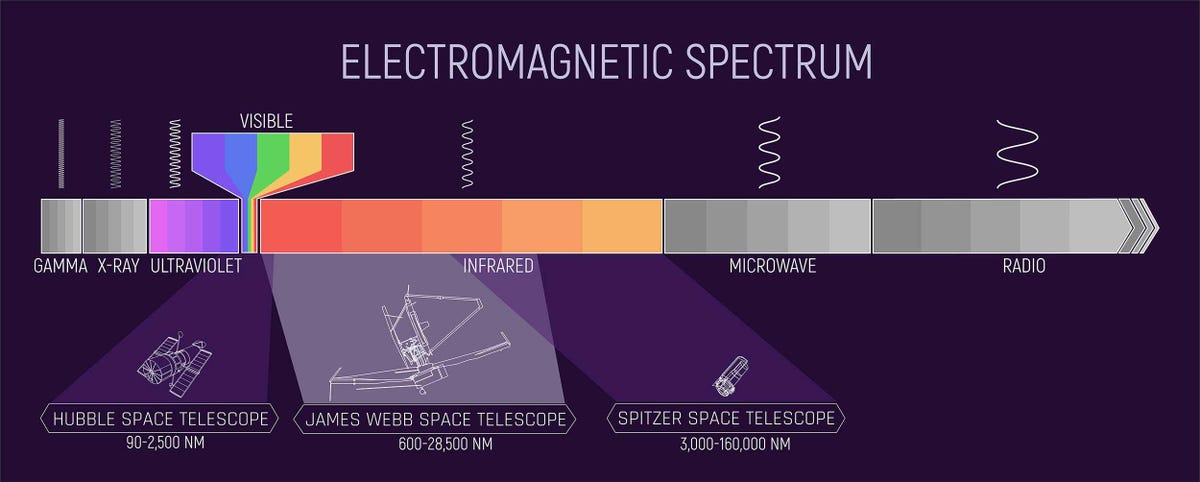

All light emanating from deep space can be categorized on a sort of diagram known as the electromagnetic spectrum. Different wavelengths of light, which also translate to different colors in our eyes, are located on different parts. On one hand you have redder wavelengths, and on the other, bluer ones.

But if you go beyond the red side of the electromagnetic spectrum, as some light indeed does, you get to infrared light.

Infrared light, unlike regular red light, is essentially invisible to human eyes. That means it’s also invisible to instruments that act like human eyes, even if they’re really powerful versions like the Hubble Space Telescope.

But infrared light is precisely the kind of light emanating from stars within most clouds of thick cosmic dust, like the veil surrounding IC 1623. So to figure out what’s going on inside, we need an infrared-light-detecting telescope. And that’s JWST.

This infographic illustrates the spectrum of electromagnetic energy, specifically highlighting the portions detected by NASA’s Hubble, Spitzer and Webb space telescopes. Spitzer is now retired, and wasn’t as high tech as the JWST is.

NASA and J. Olmsted [STScI]

As a side note, light from stars and other phenomena located really, really far away from Earth arrive at our planet as infrared light, too. That’s why the JWST is prepped to bring us information about the distant universe as it was near the beginning of time, information invisible to us and to the Hubble Space Telescope. More on that here.

Returning to IC 1623, ESA explains that “Webb’s infrared sensitivity and its impressive resolution at those wavelengths allows it to see past the dust and has resulted in the spectacular image above, a combination of MIRI and NIRCam imagery,” in reference to two of the JWST’s high-tech instruments.

Another Easter egg in this image, as with all JWST pics, is the eight-pronged diffraction spikes you see at the very center. (It looks like six spikes, but there are two mini-spikes traveling horizontally through the midpoint. They’re just hard to see). All JWST images have this signature, in contrast to Hubble’s four-pronged version.

Here’s an outline of what the JWST’s diffraction spikes look like. You’ll see these in every JWST image!

NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI), Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

In general, these spikes are super prominent when lots of light is present in an image, explaining why the telescope’s latest image of two galactic cores boasts its bright central snowflake.

Hopefully, the next time JWST focuses its lens, it’ll be on one of those sights with evidence of something we never thought to ask about.