Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) is seen next to globular star cluster M3 in this image taken by Adam Block at UArizona’s Mount Lemmon Sky Center. Credit: Adam Block/Steward Observatory/University of Arizona

The brightest comet of the year, named “Leonard” after the University of Arizona researcher who discovered it, is paying one last visit to Earth’s neighborhood this month, before leaving the solar system forever.

Now is the best time to get a glimpse of Comet C/2021 A1, better known as Comet Leonard. It’s named for its discoverer, Gregory Leonard, a senior research specialist at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

Every night with clear skies, astronomers with LPL’s Catalina Sky Survey scan the sky for near-Earth asteroids – space rocks with the potential of venturing close to Earth at some point.

During one such routine observation run on Jan. 3, Leonard spotted a fuzzy patch of light tracking across the starfield background in a sequence of four images taken with the 1.5-meter telescope at the summit of Mount Lemmon. The dot’s fuzzy appearance, combined with the fact that it had a tail, was a dead giveaway that he was looking at a comet, he said.

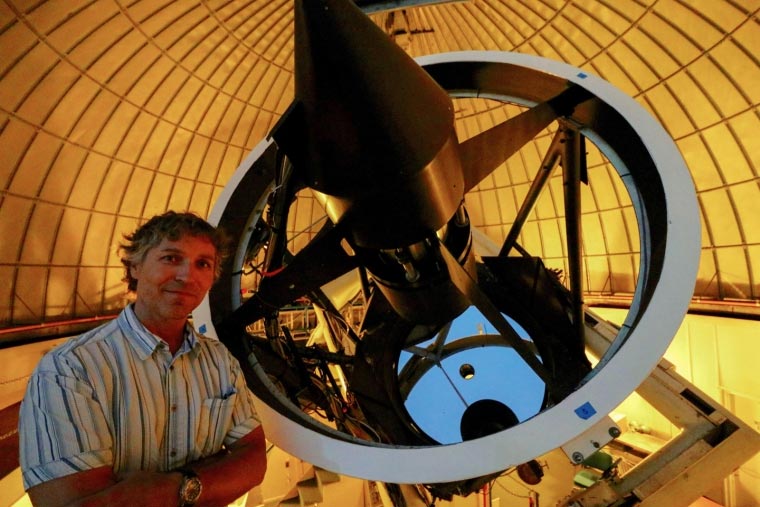

Gregory Leonard discovered the comet using the Catalina Sky Survey’s 1.5-meter (60-inch) telescope on Mount Lemmon. Credit: Camillo Scherer

“The fact that the tail showed up in those images was remarkable, considering that the comet was about 465 million miles out at that point, about the same distance as

The Catalina Sky Survey operates two telescopes at its Mount Lemmon station to search the night skies for near-Earth asteroids. Credit: David Rankin

Leonard said it is unusual for a comet to burst into activity as far out from the sun as this one did when it first showed up in Catalina Sky Survey’s 1.5-meter reflector telescope, the workhorse discovery telescope for near-Earth asteroid and many comets. At the time, it was too far out for the sun to heat water ice – the main ingredient of most comets – into a streaming tail of vapor.

“Something other than water ice was being excited by the solar radiation and producing this tenuous atmosphere – possibly frozen carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide or ammonia ices,” he said.

The comet was extremely faint, about 400,000 times dimmer than what human eyes can see, and was only picked up thanks to the combination of the telescope’s large optics and exquisitely sensitive camera. The Catalina Sky Survey operates four telescopes in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson – one pair of telescopes on Mount Bigelow and another pair on the summit of Mt. Lemmon.

Cherished for their appearance, comets are of great interest because they function as messengers from the solar system’s deep past. Preserving material left over from when the sun and planets were born, these “dirty snowballs,” as they are sometimes called, contain clues to the processes that were at work when the solar system formed.

“As much as we have great science on comets, they’re still highly unpredictable with respect to their size, shape, chemical makeup and behavior,” Leonard said. “A wise and famous comet discoverer once said: ‘Comets are like cats – both have tails and both do precisely what they want.’”