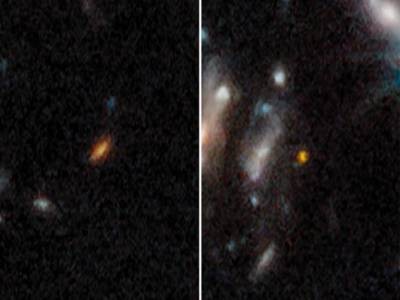

Part of the dwarf galaxy Wolf–Lundmark–Melotte (WLM) captured by the James Webb Space Telescope’s Near-Infrared Camera.Credit: Science: NASA, ESA, CSA, Kristen McQuinn (RU), Image Processing: Zolt G. Levay (STScI)

The crowd in the auditorium began murmuring, then gasping, as Emma Curtis-Lake put her slides up on the screen. “Amazing!” someone blurted out.

Curtis-Lake, an astronomer at the University of Hertfordshire, UK, was showing off some of the first results on distant galaxies from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). It was not the last time astronomers started chattering in excitement this week as they gazed at the telescope’s initial discoveries, at a symposium held at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland.

In just its first few months of science operations, JWST has delivered stunning insights on heavenly bodies ranging from planets in the Solar System to stars elsewhere in the cosmos. These discoveries have sharpened researchers’ eagerness to take more advantage of the observatory’s capabilities. Scientists are now crafting new proposals for what the telescope should do in its second year, even as they scramble for funding and debate whether the telescope’s data should be fully open-access.

White-knuckle launch

JWST launched on 25 December 2021 as the most expensive, most delayed and most complicated space observatory ever built. Astronomers held their breath as the US$10-billion machine went through a complex six-month engineering deployment in deep space, during which hundreds of potential failures could have seriously damaged it.

But it works — and spectacularly so. “I feel really lucky to be alive as a scientist to work with this amazing telescope,” says Laura Kreidberg, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

JWST spots some of the most distant galaxies ever seen

First out of the floodgate, in July, came a rush of preprints on the early evolution of galaxies. The expansion of the Universe has stretched distant galaxies’ light to infrared, the wavelengths that JWST captures. That allows the telescope to observe faraway galaxies — including several so distant that they appear as they did just 350 million to 400 million years after the Big Bang, which happened 13.8 billion years ago.

Many early galaxies spotted by JWST are brighter, more diverse and better formed than astronomers had anticipated. “It seems like the early Universe was a very profound galaxy-maker,” says Steven Finkelstein, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin.

Some of these initial findings are being revised as data calibrations improve, and many of the early claims about distant galaxies await confirmation by spectroscopic studies of the galaxies’ light. But astronomers including Curtis-Lake announced on 9 December that they have already nailed spectroscopic confirmation of two galaxies that are farther away than any ever previously confirmed.

’Mindblowing’ detail

In closer regions of the cosmos, JWST is yielding results on star formation and evolution, thanks to its sharp resolution and infrared vision. “Compared to what we can see with Hubble, the amount of details that you see in the Universe, it’s completely mind-blowing,” says Lamiya Mowla, an astronomer at the University of Toronto in Canada. Thanks to telescope’s keen vision, she and her colleagues were able to spot bright ‘sparkles’ around a galaxy that they dubbed the Sparkler; the sparkles turned out to be some of the oldest star clusters ever discovered. Other studies have unveiled details such as the hearts of galaxies where monster black holes lurk.

Another burst of JWST discoveries comes from studies of exoplanet atmospheres, which the telescope can scrutinize in unprecedented detail.

JWST reveals first evidence of an exoplanet’s surprising chemistry

For instance, when scientists saw the first JWST data from the exoplanet WASP-39b, signals from a range of compounds, such as water, leapt right out. “Just looking at it was like, all the answers were in front of us,” says Mercedes López-Morales, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Now scientists are keenly anticipating data about other planets including the seven Earth-sized worlds that orbit the star TRAPPIST-1. Early results on two of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, reported at the symposium, suggest that JWST is more than capable of finding atmospheres there, though the observations will take more time to analyse.

JWST has even made its first planet discovery: a rocky Earth-sized planet that orbits a nearby cool star, Kevin Stevenson at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, told the meeting.

The telescope has also proved its worth for studying objects in Earth’s celestial neighbourhood. At the symposium, astronomer Geronimo Villanueva at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, showed new images of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Scientists knew that Enceladus has a buried ocean whose water sometimes squirts out of fractures in its icy crust, but JWST revealed that the water plume envelops the entire moon and well beyond. Separately, engineers have also figured out a way to get JWST to track rapidly moving objects, such as Solar System planets, much better than expected. That led to new studies such as observations of the DART spacecraft’s deliberate crash into an asteroid in September, says Naomi Rowe-Gurney, an astronomer also at Goddard.

Fresh images reveal fireworks when NASA spacecraft ploughed into asteroid

Yet all these discoveries are but a taste of what JWST could ultimately do to change astronomy. “It’s premature to really have a full picture of its ultimate impact,” says Klaus Pontoppidan, JWST project scientist at STScI. Researchers have just begun to recognize JWST’s powers, such as its ability to probe details in the spectra of light from astronomical objects.

Applications are now open for astronomers to pitch their ideas for observations during JWST’s second year of operations, which starts in July. The next round could result in more ambitious or creative proposals to use the telescope now that astronomers know what it is capable of, Pontoppidan says.

Amid all the good news, there are still glitches. Primary among them is a lack of funding to support scientists working on JWST data, says López-Morales. “We can do the science, we have the skills, we are developing the tools, we are going to make groundbreaking discoveries but on a very thin budget,” she says. “Which is not ideal right now.”

Available to all?

López-Morales chairs a committee that represents astronomers who use JWST, and their to-do list is long. It includes surveying scientists about whether all of the telescope’s data should be freely available as soon as it is collected — a move that many say would disadvantage early-career scientists and those at smaller institutions who do not have the resources to pounce on and analyse JWST data right away. Telescope operators are also working on a way to get its data to flow more efficiently to Earth through communication dishes, and to fly it in a physical orientation that reduces the risk of micro-meteoroids smashing into and damaging its primary mirror.

But overall the telescope is opening up completely new realms of astronomy, says Rowe-Gurney: “It’s the thing that’s going to answer all the questions that my PhD was trying to find.”