Once the troublesome element of the Constellation (now Artemis) Program, three Orion spacecraft are in various stages of preparation for flight, two of which now already reside at their Kennedy Space Center launch site.

With the Artemis 3 Orion – set to depart Earth with the crew that will step foot on the surface of the Moon – now being constructed at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF), Orion’s multi-billion dollar journey to transporting humans into deep space is back on track.

Orion’s Painful Childhood:

Orion’s development has been ongoing as long as NASASpaceflight.com has been on the internet – with the site recently celebrating its 16th birthday.

At the time, the Space Shuttle fleet was returning to flight with a final swansong of missions that would complete assembly of the International Space Station (ISS) before Orion – then called the CEV (Crew Exploration Vehicle) – was scheduled to take over ISS crew rotations before heading out on missions to the Moon and Mars.

This was called the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) – “Moon, Mars and Beyond” – and was based on a schedule that resulted in a short gap between the end of the Shuttle and Orion entering operation.

The keep the gap to a minimum, NASA opted for the utilization of former Shuttle hardware to be included in the rocket architecture, with the Ares I launch vehicle as a single five-segment Solid Rocket Booster “Stick” design that would be joined by the Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle (HLV) Ares V, which is akin to what SLS has since become.

Ares I and Ares V, a 1.5 launch system architecture for LEO and BEO missions. NASA render.

However, Ares I provided the greatest challenges during the Constellation Program (CxP) during the early phase, impacting Orion. While the changes were part of any new spacecraft’s natural evolution, the main challenges were associated with “mass reserves” and shortfalls in Ares I’s performance.

This, in turn, forced Orion to shed weight in a painful and obstructive series of exercises, almost immediately causing the CEV to reduce its diameter by 0.5 meters, soon followed by its Service Module being stripped down by up to 50% of its original mass.

Provided with the name “Orion,” engineers at Lockheed Martin – the vehicle’s prime contractor – were told to reduce the spacecraft’s mass further, resulting in a cull of the amount of propellant the vehicle would carry during International Space Station (ISS) missions – the initial role for Orion.

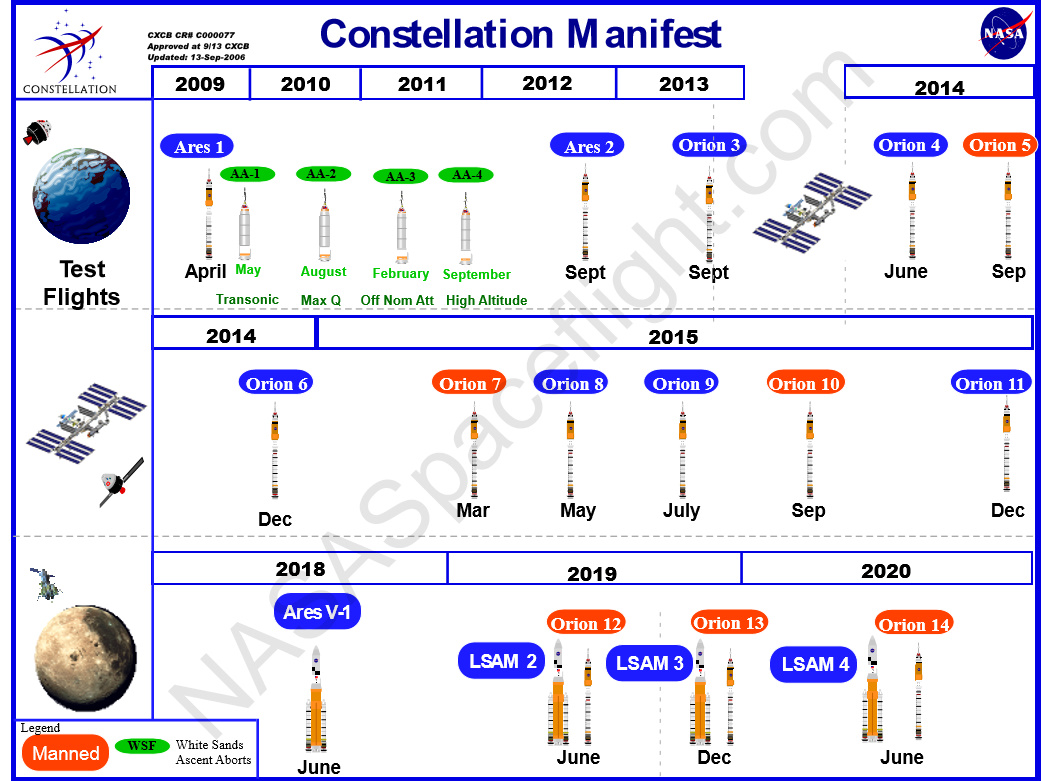

The CxP manifest, created in 2005 and acquired by NSF L2

In what seemed to be a never-ending series of demands, Orion lost its ability to use an airbag system to land on terra firma, reverting to Apollo-style water landings.

Other advanced systems – part of the “Apollo on Steroids” ideal of creating a super capsule far more capable than its predecessor – were also removed from the vehicle.

With frustrations growing between Ares I – which also claimed the design changes were hindering it – and Orion, project managers held a summit in 2007 and decided they would strip Orion down to a “minimum requirement” spacecraft, thus allowing Ares I some breathing space to work within several thousand pounds of mass reserves.

Orion lost its airbag landing capability due to mass issues – via NASA

Orion underwent a mass ‘scrubbing’ process to reduce it to a minimum weight, ahead of the reapplication of some of the deleted capability, element by element. The project noted it was using the Block 2 “Lunar Orion” for this exercise, as much as the results were to be fed into the Block 1 “ISS Orion.”

With CxP starting to show signs it was going to have to slip its schedule, an All Hands meeting at the end of 2007 referenced the need for “teamwork and chemistry,” with then-Ares program manager Steve Cook warning, “Failure is an option during development,” while a System Definition Review (SDR) Board meeting noted major “red” risks in controlling Orion’s weight to match Ares I performance.

In 2008, the Orion Vehicle Engineering Integration Working Group (OVEIWG) began to reinstall some of the “critical capability” back onto the vehicle without breaching strict mass requirements. Some engineers joked the Group was providing the role of Ken Mattingly when he juggled limited amps as he created a power-up sequence for the crippled Apollo 13 capsule via testing in a simulator.

Ironically, it was Apollo 13 Flight Director Gene Kranz who issued a stirring speech to the Constellation workforce (video in L2) that year, noting how the Apollo workforce “had to learn to leave our egos at the door and become a team, so we became one.”

By the middle of 2008, a new Design Analysis Cycle (DAC) was called for in tandem with efforts to resolve Thrust Oscillation (TO) issues – resulting in a major slip to the vehicle’s Preliminary Design Review (PDR) to 2009.

One of the options to reduce Thrust Oscillation on the crew – a pallet (adding yet more mass) – via NASA

With the additional stresses of a reduced budget for Constellation, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) called for the Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee in 2009 – better known as the Augustine Commission.

The review highlighted CxP’s critical issues, ultimately resulting in its cancellation by the Obama administration via the FY2011 Budget Proposal.

Orion Realignment:

Orion was saved from the CxP cull, albeit in stages – including a near-pointless role as a very expensive lifeboat for the ISS – before the 2010 Authorization Act refocused Orion on Beyond Earth Orbit (BEO) missions.

The first physical sign of Orion’s new life was seen at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF), as the Exploration Flight Test -1 (EFT-1) vehicle saw its first panels welded together.

With NASA representing the start of construction as “the first new NASA spacecraft built to take humans to orbit since space shuttle Endeavour left the factory in 1991,” the EFT-1 Orion enjoyed a successful build in New Orleans before heading to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) for outfitting.

EFT-1 proved to be a success, launching atop the Delta IV-Heavy on a mission that played a major role in allowing Orion to pass Critical Design Reviews (CDRs) and enter a production cadence.

Nevertheless, challenges were still found with the European Space Agency’s commitment to provide the Service Module elements; however, that too is now back on track.

Artemis 1 Orion:

Set to launch on the first flight of SLS, the Artemis 1 Orion spent a lengthy time “mothballed” in the O&C (Operations & Checkout) Building at the Kennedy Space Center.

Finally, in a major milestone for the spacecraft, Orion was moved to the Multi-Payload Processing Facility (MPPF) for fueling operations.

However, with the delay to the SLS launch date, Orion engineers had to be wary about pushing Orion through hypergolic loading tasks due to a 400-day clock that begins once the vehicle is fuelled.

Artemis-1 Orion ahead of Hypergolic loading – via NASA

The team completed the first ammonia tank servicing on February 26, 2021, and the second ammonia tank on March 2, 2021. Both tanks were filled with 32 pounds of ammonia ahead of a boiler functional test. After the functional testing, the tanks were then drained and refilled to final flight tank commodity requirements.

That final “go” for hypergolic loading was further held after the aborted SLS Green Run Static Fire test. With the Core Stage having now passing its four-engine firing at Stennis, fueling operations can now occur.

The run-up to hypergolic loading saw engineers sample the fueling hoses prior to vehicle mate to meet the contamination specifications. This set up a March 23 loading event, although competition of that task has yet to be confirmed by NASA.

The Artemis 1 Orion is currently housed next to the ULA-provided Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS). The two hardware elements will be mated and then rolled to the VAB for stacking with SLS on Mobile Launcher -1 (ML-1).

Artemis-1 Orion next to its ICPS in the MPPF via NASA

NASA is yet to rule out a launch by the end of this year. However, internal schedules point to a February 2022 launch being the most realistic target.

Artemis 2 Orion:

The second Orion is already at KSC, a spacecraft tasked with repeating Artemis 1’s uncrewed flight around the Moon, but this time with a crew of four onboard.

Recent work has revolved around environmental control and life support system (ECLSS) subassembly installations and fit checks in addition to welding operations.

Artemis-2 Orion inside the KSC O&C via NASA

The crew module underwent work in the cleanroom in the O&C Building for the completion of over 100 welds on the ECLSS and propulsion systems. Click bonds on forward walls 3 and 4 for the Optical Communication System (OpCom) – which will provide Orion with a high rate communication system for Artemis 2 – is also being worked on.

The Artemis 2 Crew Module was then moved into the Crew Module Station to enable the installation of several environmental control systems components, while the Crew Module Adapter (CMA) was moved into the cleanroom for completion of welding operations.

The Service Module is currently being worked on in Bremen, Germany – which recently saw the installation and checkout of the OME (Orbital Maneuvering System) engine that had previously flown with Shuttle Atlantis.

Shuttle Atlantis to the Moon!

The engine for the second European Service Module (ESM) for Orion Artemis-2 crewed mission around the moon has been installed at Airbus facilities in Germany.

It previously flew as an OME on Atlantis.@esa link:https://t.co/QhyK0mXqEc pic.twitter.com/yA1wY90zBC

— Chris B – NSF (@NASASpaceflight) March 25, 2021

While active thermal control system loop B testing is completed, planned activities include OME engine thrust vector system checkout and gimbal testing to confirm that all electronic system signals are correctly interpreted and whether all mechanical components are working as planned.

Artemis 3:

This Orion will be tasked with transporting the first crew on a Lunar Landing mission involving the first use of the Human Landing System (HLS).

Following the roadmap of previous Orions, assembly is taking place at the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans.

The first three-cone panel welds on the Artemis 3 crew module pressure vessel were completed on January 20, 2021. The final element of the crew module pressure vessel – the tunnel – then underwent its forward bulkhead weld, while engineers worked in parallel on set up for the following barrel-to-aft bulkhead weld activities.

Welding the panels on the Artemis-3 Orion – via NASA

Initial non-destructive evaluation (NDE) data and visual inspections of the welds were noted to be good, allowing progress to move to the barrel-to-aft bulkhead weld.

While the Crew Module Assembly inner wall is making good progress in machining at its contractor in Illinois, MAF engineers moved into plug welds and planishing tasks.

The Service Module for Artemis 3 is also making good progress, with the Airbus team in Bremen, Germany, working through active thermal control system (ATCS) Loop B testing. ATCS testing sets the stage for Orbiter Maneuvering System engine installation.

It is unknown which OME will be involved with Artemis 3’s service module, although it will be one of the stock of donated engines from the Space Shuttle era.