These days, NASA deciding to launch one of their future missions on a commercial rocket is hardly a surprise. After all, the agency is now willing to fly their astronauts on boosters and spacecraft built and operated by SpaceX. Increased competition has made getting to space cheaper and easier than ever before, so it’s only logical that NASA would reap the benefits of a market they helped create.

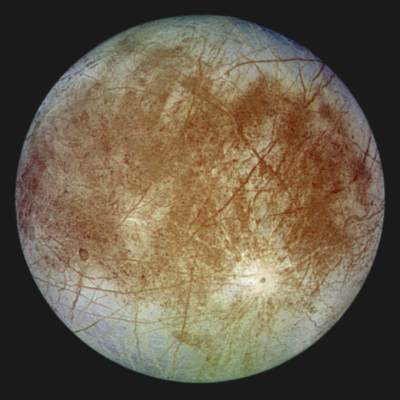

So the recent announcement that NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will officially fly on a commercial launch vehicle might seem like more of the same. But this isn’t just any mission. It’s a flagship interplanetary probe designed to study and map Jupiter’s moon Europa in unprecedented detail, and will serve as a pathfinder for a future mission that will actually touch down on the moon’s frigid surface. Due to the extreme distance from Earth and the intense radiation of the Jovian system, it’s considered one of the most ambitious missions NASA has ever attempted.

With no margin for error and a total cost of more than $4 billion, the fact that NASA trusts a commercially operated booster to carry this exceptionally valuable payload is significant in itself. But perhaps even more importantly, up until now, Europa Clipper was mandated by Congress to fly on NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). This was at least partly due to the incredible power of the SLS, which would have put the Clipper on the fastest route towards Jupiter. But more pragmatically, it was also seen as a way to ensure that work on the Shuttle-derived super heavy-lift rocket would continue at a swift enough pace to be ready for the mission’s 2024 launch window.

But with that deadline fast approaching, and engineers feeling the pressure to put the final touches on the spacecraft before it gets mated to the launch vehicle, NASA appealed to Congress for the flexibility to fly Europa Clipper on a commercial rocket. The agency’s official line is that they can’t spare an SLS launch for the Europa mission while simultaneously supporting the Artemis Moon program, but by allowing the Clipper to fly on another rocket in the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress effectively removed one of the only justifications that still existed for the troubled Space Launch System.

To Europa, Eventually

There’s no question that the SLS, at least on paper, would have been the ideal vehicle to carry the Europa Clipper on its epic journey. The megarocket would have enough energy to send the roughly 6,065 kg (13,371 lb) probe on a direct trajectory towards Jupiter during its closest pass in 2024, which would bring the planet within 611 million kilometers (380 million miles) of Earth. On this flight path, it would take a little less than three years for the Clipper to enter orbit around Jupiter and begin its scientific mission.

Unfortunately, there’s simply no replacement for the SLS in terms of raw power. While future vehicles from SpaceX, Blue Origin, and United Launch Alliance could be compelling options, they simply won’t be ready in time for the 2024 launch window. Even if they’re operational by then, which is by no means a guarantee, they certainly won’t have enough flights logged to prove their reliability. NASA could conceivably wait until one of the later launch windows in 2025 or 2026 to give commercial operators more time to bring their next-generation heavy lift vehicles online, but at least for now, that’s not in the cards.

So how do you get to Europa without the massive boost provided by the SLS? In a word, slowly. While there was some previous speculation that the spacecraft could be fitted with a small “kick stage” to make up for the reduced initial velocity, the preliminary launch contract information provided by NASA specifies that the spacecraft will make use of gravity assist maneuvers by flying what’s known as a Mars-Earth-Gravity-Assist (MEGA) trajectory. This will allow the Europa Clipper to reach its destination without any hardware modifications, but the downside of this complex orbital dance is that the journey will take more than twice as long to complete, with the probe not reaching Europa until 2030 at the earliest.

No determination has yet been made as to which rocket will ultimately launch the Clipper, and the decision isn’t likely to come until next year after the completion of a formal selection process. That said, as it has the highest payload capacity of any currently operational rocket in the world, the SpaceX Falcon Heavy is far and away the most likely choice. Even still, it will potentially have to launch in the as of yet unused fully expendable mode.

So Long, Shelby

This first public acknowledgement that NASA is no longer planning to fly Europa Clipper on the Space Launch System comes just days after Alabama Senator Richard Shelby, one of the SLS program’s staunchest supporters, announced he would be retiring next year. Concerned that President Obama’s 2010 cancellation of the Constellation program would mean the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama would no longer be the center of America’s spaceflight industry, Senator Shelby fought hard to make sure SLS would be a flagship program to rival the Saturn V and Space Shuttle:

While few would complain about politicians taking an active interest in space exploration, and keeping hundreds of high-paying aerospace jobs in his district was a commendable achievement, Shelby’s support of NASA came at a cost. He has been vehemently opposed to NASA’s partnerships with commercial launch providers, going so far as to call the agency’s early contracts with companies like SpaceX a “faith-based initiative” and “a welfare program for the commercial space industry” as the fledgling aerospace firms had yet to demonstrate they could actually build a booster capable of reaching orbit.

It’s a safe bet that Senator Shelby’s replacement will take a similarly bullish approach to Marshall Space Flight Center, but it’s difficult to imagine they will be able to ignore the leaps and bounds made by commercial launch providers in the last few years. As private industry rapidly iterates through cutting-edge engine and booster technology, the Space Launch System’s reliance on Shuttle-derived hardware conceived in the 1970s only becomes harder to defend.

Difficult Decisions Ahead

Between the embarrassing “Green Run” failure in January, the loss of the Europa Clipper mission, and the retirement of Senator Shelby, the future of the Space Launch System has never been more uncertain. Add in a White House that’s far more concerned with fighting a deadly pandemic than leaving new boot prints on Mars or the Moon, and it’s not hard to see how the oft-delayed and incredibly expensive program might finally be running out of road.

To be sure, the SLS will fly at least once. NASA and Boeing are getting ready to repeat the failed engine test in the next few weeks, and too much time and money has been invested to not go ahead with the Artemis I mission. Even if NASA ultimately decides to wind down the SLS program in favor of further commercial cooperation, the shakedown flight is just as much a test of the Orion crew vehicle. With several more Orion capsules already under construction for future Artemis missions, development of the Apollo-like capsule is almost certainly going to continue with or without the SLS.