Researchers investigating the genetic make-up of the monkeypox virus have said the virus appears to have mutated far, far more than would normally be expected.

The work has been outlined in a new study published in the journal Nature Medicine. As part of the study, Portuguese researchers collected 15 monkeypox virus sequences in total—mostly from Portugal—and reconstructed their genetic data.

Monkeypox is a rare disease believed to have its origin in animals. It is from the same family of viruses as smallpox. Usually monkeypox is localized within West and Central African countries but this year has seen the first multi-country outbreak, including cases without known links to West or Central Africa, with more than 3,500 cases reported as of Thursday, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The virus can be transmitted between people by close contact with lesions, body fluids, respiratory droplets—such as via face-to-face contact—and contaminated materials. The current outbreak has introduced uncertainty about exactly how the virus is spreading, with far more transmission than is normal.

In the latest study, researchers discovered around 50 genetic variations in the viruses they studied compared to ones from 2018 and 2019. This, they said, “is far more than one would expect considering previous estimates” of the mutation rate of orthopoxviruses of which monkeypox is a type—between six and 12 times more.

These significant genetic variations might suggest “accelerated evolution.”

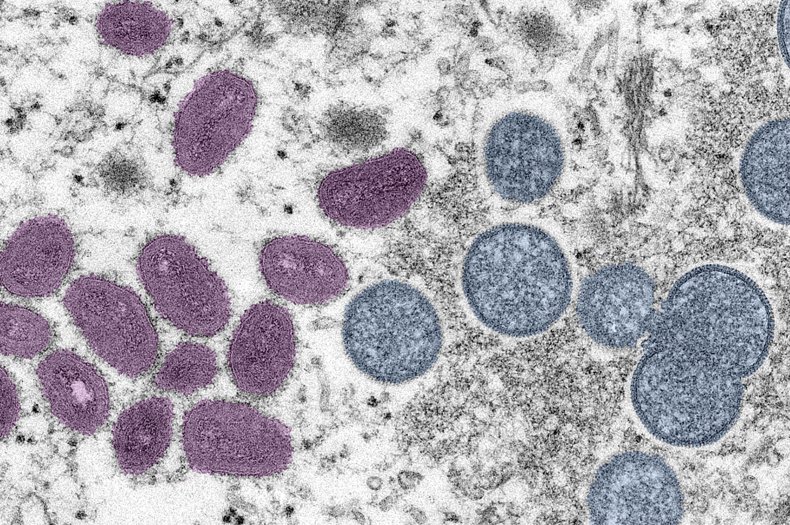

Getty Images

“Our data reveals additional clues of ongoing viral evolution and potential human adaptation,” the team wrote, adding that they had identified proteins that are known to interact with peoples’ immune systems. However, more studies will be needed to find out more about the potential role these might play in adapting the monkeypox virus for human spread.

João Paulo Gomes, head of the Genomics & Bioinformatics Unit at the National Institute of Health in Portugal who co-authored the study, said it is not known whether the mutations have contributed to increased transmissibility between people.

“We do not know that,” he told Newsweek. “We just know that these additional 50 mutations were quite unexpected.

“Considering that this 2022 monkeypox virus is likely a descendant of the one in the 2017 Nigeria outbreak, one would expect no more than five to 10 additional mutations instead of the observed about 50 mutations. We hope that now, specialized groups will perform laboratory experiments in order to understand if this 2022 virus has increased its transmissibility.”

Another notable finding from the study is that most of the mutations are of a particular type that could have been introduced by a human defence mechanism called APOBEC3, which works by introducing mutations to viruses in order to stop them from working properly, said Pam Vallely, professor of medical virology at the University of Manchester.

“However, in this case the mutations are apparently not making the virus non-viable and may be helping it to adapt to human-human transmission,” Vallely, who was not involved in the study, told Newsweek. “This is just a theory that fits the current evidence, and lots more work is going to be needed to see if this is what is really happening. I don’t think we can say the mutations have made it more contagious, but maybe they have made it better adapted to humans.”

The researchers say their work shows that viral genome sequencing of monkeypox might be precise enough to track the spread of the current outbreak and see how transmission might be changing. This, in turn, would allow decision makers to introduce measures to curb monkeypox spread. Vaccines are already available.

CDC/Goldsmith/Smith Collection/Gado/Getty

Jeremy Kamil, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek the study as “very impressive” but said it is too early to say for sure whether monkeypox is undergoing rapid evolution until we can rule out the possibility that the virus has been circulating and adapting in people “for longer than people assume—perhaps starting out in undersampled regions of the world like parts of Africa where monkeypox is endemic.”

Alex Sigal, a virologist at the Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI) and associate professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, who was also not involved in the study, echoed Kamil’s point.

“I think this outbreak was under the radar for a while,” he told Newsweek. “Certainly the diminishing immunity because the smallpox vaccine is no longer given could have helped.

“[The findings are] concerning, but we’ll see if this virus keeps spreading once people start to be aware of the signs and it breaks out in the general population. It’s contact dependent, and unless spread goes respiratory, it should be easier to stop.”

Virus sequencing efforts also confirmed that the viruses studied belonged to a specific type of monkeypox virus known as clade 3, confirming them to be part of the wider West African type as opposed to the Central African type.

The West African version of monkeypox, with a case fatality ratio of usually less than one percent, is much less virulent than the Central African clade 1 version which can cause death in more than 10 percent of cases, according to the study.

Update, 6/24/22, 6:13 a.m. ET: This article has been updated with the most recent monkeypox case numbers.