Beyond some of the iffy stuff in the headlines today.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

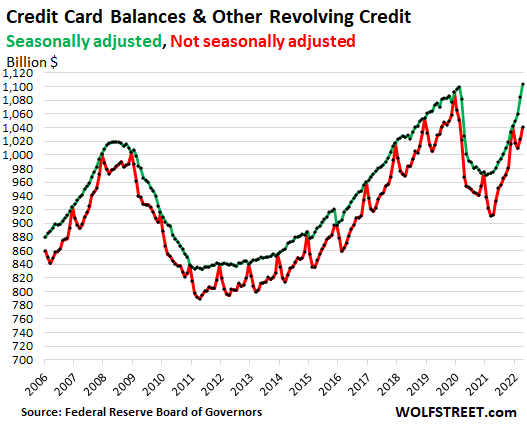

Revolving credit balances in April, not seasonally adjusted – so the actual dollar balances – were $1.04 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve this afternoon. This includes credit card balances, personal loans, etc., and was up by only 2.6% from April 2019.

Let that sink in for a moment: Over a three-year period, revolving credit has grown by only 2.6%, despite 13% CPI inflation over those three years. In other words, the growth in revolving credit has fallen sharply in inflation adjusted terms.

The huge trough between 2019 and today stems from the pandemic when consumers used their stimulus money to pay down credit cards, and when they cut spending on discretionary services, such as sports and entertainment events, international travel, or elective healthcare services such as cosmetic surgery, dentist visits, etc. Over this period, delinquencies dropped to record lows.

Revolving credit balances are barely above the peaks of 2007 and 2008, despite 14 years of population growth and 40% CPI inflation over those years! In other words, revolving credit just isn’t the kind of issue it was in 2008. It’s a sideshow.

In terms of growth – in terms of additional borrowed money spent in the economy – it was minuscule. There was in fact no growth since December. And after the pay-downs in January and February, following the annual holiday shopping binge, the total balances only grew by $14 billion in March and by $17 billion April, for a combined $31 billion.

This growth of $31 billion in March and April didn’t even make up for the $32 billion in pay-downs in January and February. These are actual dollars, not seasonally adjusted theoretical dollars.

In terms of adding to the growth of the economy: Total consumer spending is currently running at an annual rate of $17 trillion, with a T. So how much growth would the additional spending from the increase in revolving credit add? That was a rhetorical question. It’s minuscule.

Since 2019, consumer spending has increased 19%, and revolving credit has increased only 2.9%, both not adjusted for 13% inflation over the period. In other words, growth in revolving credit fell sharply behind inflation and fell massively behind growth in consumer spending.

This shows that consumers are relying less on revolving credit.

Credit cards and some types of personal loans, such as payday loans, are the most expensive form of credit, and they often come with usurious interest rates. Credit card rates can exceed 30%. And Americans have figured this out. If they need to fund purchases, many consumers use cheaper loans, including cash-out refinancing of their mortgages.

And many, many consumers are using their credit cards just as payment methods, and they pay them off every month. That’s what these relatively low balances show.

The beautiful seasonal adjustments.

The seasonal adjustments to the actual revolving credit dollar balances are designed to match up with the peak month every year, namely December. In other words, there are no seasonal adjustments for December, but the other 11 months are always adjusted upward, as if every month were a December during peak holiday shopping binge. And this creates the bizarre pattern where during 11 months of the year, the seasonal adjustments grossly overstate the actual revolving credit balances.

In this chart the green line represents the seasonally adjusted balances. Note how it rides on top of all the Decembers. The red line represents the actual balances, not seasonally adjusted. And note the crazy disconnect between the two lines over the past four months:

The data on consumer credit that the Federal Reserve released today was its limited monthly set, just two incomplete summary categories of a complex phenomenon: “revolving credit,” which I discussed above, and “nonrevolving credit,” which is composed of auto loans and student loans combined, but not separated out, and it doesn’t include mortgages, HELOCs and other debts.

The individual categories of auto loans, student loans, mortgages, and HELOCs are released only quarterly by the New York Fed, and I discussed them for Q1, covering every category, including mortgages and HELOCs, plus delinquency rates for every category, plus third-party collections, foreclosures, and bankruptcies, as part of my quarterly review of consumer credit in America.

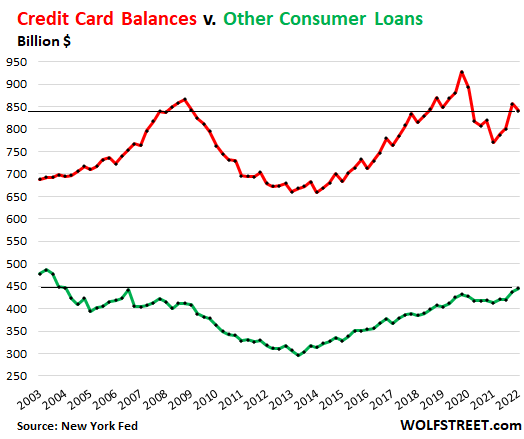

This quarterly data shows credit card balances by themselves, plus other revolving consumer loans:

- Credit card balances at $840 billion in Q1, were back where they’d been in Q1 2008, and below Q1 2020 and Q1 2019, (red line).

- Other consumer loans (personal loans, payday loans, etc.), at $450 billion, were below the levels well before the Financial Crisis (green line):

In other words, revolving consumer credit was roughly flat with 13 years ago, despite 13 years of population growth and 40% inflation. In real terms and per capita, it has become a sideshow.

Sure, some people are in over their heads, and they’ll fall behind. That always happens. But in the overall credit risk spectrum, this just isn’t a big issue anymore. Consumers have gotten a lot smarter since the Financial Crisis. They’re borrowing via much cheaper mortgage loans and auto loans, and proportionately much less at these rip-off rates that come with credit card and personal loans.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.