Gas companies and utilities are in a pickle. Their entire business model relies on the extraction, transport, and combustion of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases known to humankind. With many countries aiming to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, these companies face an uncertain future.

One solution they’ve proposed is slipping hydrogen into their distribution lines, either partially or fully replacing natural gas, so that people can burn it to heat their homes or generate electricity. When produced using solar and wind power, hydrogen is a zero-carbon fuel, and while refitting natural gas infrastructure would be expensive, it would give gas-only utilities a reason to exist.

The problem is that producing so-called “green” hydrogen is expensive and will remain so for a decade or more, according to forecasts.

To buy themselves time, utilities and oil and gas companies have proposed producing hydrogen from natural gas. Most hydrogen today is made by exposing natural gas to high heat, pressure, and steam in a process that creates carbon dioxide as a byproduct. In what’s called “gray” hydrogen, all that carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. In “blue” hydrogen, facilities capture the carbon dioxide and sell it or store it, usually deep underground.

Blue hydrogen is viewed by some as a bridge fuel, a way to build the hydrogen economy while waiting for green hydrogen prices to come down. In the meantime, blue hydrogen is also supposed to pollute less than gray hydrogen, natural gas, or other carbon-intensive fuel sources.

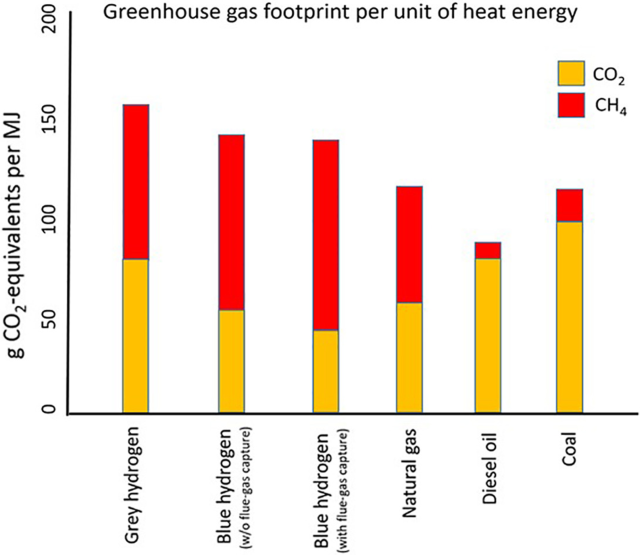

Except blue hydrogen may not be low-carbon at all, according to a new peer-reviewed study. In fact, the study says the climate may be better off if we just burned coal instead.

Achilles’ heel

There are essentially two ways to make blue hydrogen, and both rely on steam reformation, the process of using high heat, pressure, and steam that cracks methane and water to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide. For both approaches, carbon dioxide from steam reformation is captured and stored or used. The difference between the two is whether carbon dioxide is captured from the generators that power the steam-reformation and carbon-capture processes.

When you add it all up, capturing carbon from all parts of the process—steam reformation, power supply, and carbon capture—eliminates just 3 percent of greenhouse gas emissions compared with only capturing carbon from steam reformation. The lowest-carbon blue hydrogen had emissions that were just 12 percent lower than for gray hydrogen.

Blue hydrogen’s Achilles’ heel is the methane used to produce it. Methane is the dominant component of natural gas, and while it burns more cleanly than oil or coal, it’s a potent greenhouse gas on its own. Over 20 years, one ton of the stuff warms the atmosphere 86 times more than one ton of carbon dioxide. That means leaks along the supply chain can undo a lot of methane’s climate advantages.

Anyone who lives in an area with old pipelines knows that gas leaks are an unfortunate reality. Methane is a small molecule, and it’s great at finding cracks in the system. Gas wells and processing facilities are also pretty leaky. Add it all up, and anywhere between 1-8 percent of all energy-related methane escapes into the atmosphere, depending on where and how it’s measured.

In the new study, Robert Howarth and Mark Jacobson, the paper’s authors and two well-known climate scientists, assume a leakage rate of 3.5 percent of consumption. They arrived at that number by scouring 21 studies that surveyed the emissions of gas fields, pipelines, and storage facilities using satellites or airplanes. To see how their 3.5 percent rate affected the results, Howarth and Jacobson also ran their models assuming 1.54 percent, 2.54 percent, and 4.3 percent leakage. Those rates are based on EPA estimates at the low end and, at the high end, stable carbon isotope analysis that isolated emissions from shale gas production.

No matter which leakage rate they used, blue hydrogen production created more greenhouse gas equivalents than simply burning natural gas. And at the 3.5 percent leakage rate, blue hydrogen was worse for the climate than burning coal.

“Combined emissions of carbon dioxide and methane are greater for gray hydrogen and for blue hydrogen (whether or not exhaust flue gases are treated for carbon capture) than for any of the fossil fuels,” Howarth and Jacobson wrote. “Methane emissions are a major contributor to this, and methane emissions from both gray and blue hydrogen are larger than for any of the fossil fuels.”

Questionable policies

The new carbon accounting may undermine some countries’ climate plans, particularly the UK’s. Prime Minister Boris Johnson is expected to announce a plan in the coming weeks that would shift the country’s energy sector away from natural gas toward a mix of blue and green hydrogen. The government has said it wants 5 GW of “low-carbon” hydrogen capacity by the end of the decade. Oil and gas giants BP and Equinor, taking a cue from government announcements, both announced plans for massive blue hydrogen plants in the country with outputs of 1 GW and 1.2 GW, respectively.

The new study also casts doubt on some plans to shift transportation to hydrogen. Some sectors, like freight and aviation, may end up requiring hydrogen for certain routes. But cars and trucks, which many countries say must be zero-emitting by 2035 or sooner, will have a harder time justifying a switch to hydrogen over straight electrification. Companies that have bet their future on hydrogen, like Toyota, are in a tight spot as their bridge to a truly zero-carbon portfolio takes a hit.

Not all hydrogen suffers from these problems, of course. Green hydrogen, which is made by splitting water using wind or solar power, doesn’t suffer from the same carbon accounting issues. But neither does it reuse oil and gas companies’ existing infrastructure. So while this new study seems to be a pretty damning indictment of blue hydrogen, it’s unlikely to be the final nail in its coffin.