Cretapsara athanata: The first crab in amber from the dinosaur era. Credit: Xiao Jia (Longyin Amber Museum)

Discovery provides new insights into the evolution of crabs and when they spread around the world

Looking at the ancient piece of amber, Javier Luque’s first thought wasn’t whether the crustacean trapped inside could help fill a crucial gap in crab evolution. He just, more or less, wondered what the heck is a crab doing stuck in fossilized tree resin?

“In a way, it’s like finding a shrimp in amber,” said Luque, a post-doctoral researcher in the Harvard Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. “Talk about wrong place, wrong time.”

Luque spent three years trying to unravel the puzzle and, along with a team of international scientists, reported the findings on today (October 20, 2021) in Science Advances.

Artistic reconstruction of Cretapsara athanata: The immortal Cretaceous spirit of the clouds and waters. Credit: Artwork by Franz Anthony, courtesy of Javier Luque (Harvard University).

They say the 100-million-year-old piece of amber, recovered from the jungles of Southeast Asia, holds what’s believed to be the oldest modern looking crab ever found. The discovery provides new insights into the evolution of these crustaceans and when they spread around the world.

The 5-millimeter crab is the first-ever found in amber from the dinosaur era, and the researchers think it represents the oldest evidence of incursions into non-marine environments by “true crabs.”

True crabs (known as Brachyurans) stand in contrast to “false crabs” (called Anomurans) that aren’t technically crabs but are still sometimes called by the name (think hermit crabs or king crabs).

Previous fossil records, which mainly consist of bits and pieces of claws, suggested that nonmarine crabs came onto land and freshwater about 75 to 50 million years ago. This new discovery pushes that back to at least 100 million years ago, answering Luque’s initial question of what this crab was doing in the jungle and bringing the fossil record in line to long-held theories on the genetic history of crabs.

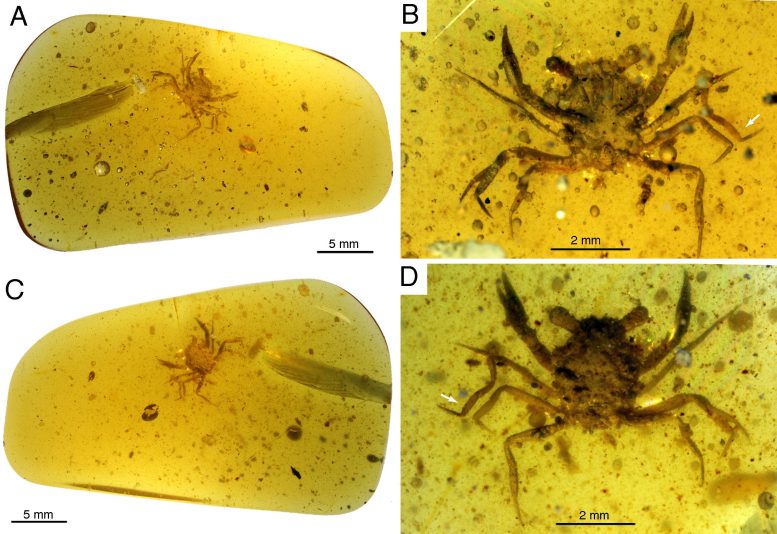

1. C. athanata Luque gen. et sp. nov., a modern-looking eubrachyuran crab in Burmese amber. (A to D) Holotype LYAM-9. (A) Whole amber sample with crab inclusion in ventral view. (B) Close-up of ventral carapace. (C) Whole amber sample with crab inclusion in dorsal view. (D) Close-up of dorsal carapace. White arrows in (B) and (D) indicate the detached left fifth leg or pereopod. Credit: Images and figure by Javier Luque and Lida Xing

“If we were to reconstruct the crab tree of life — putting together a genealogical family tree — and do some molecular

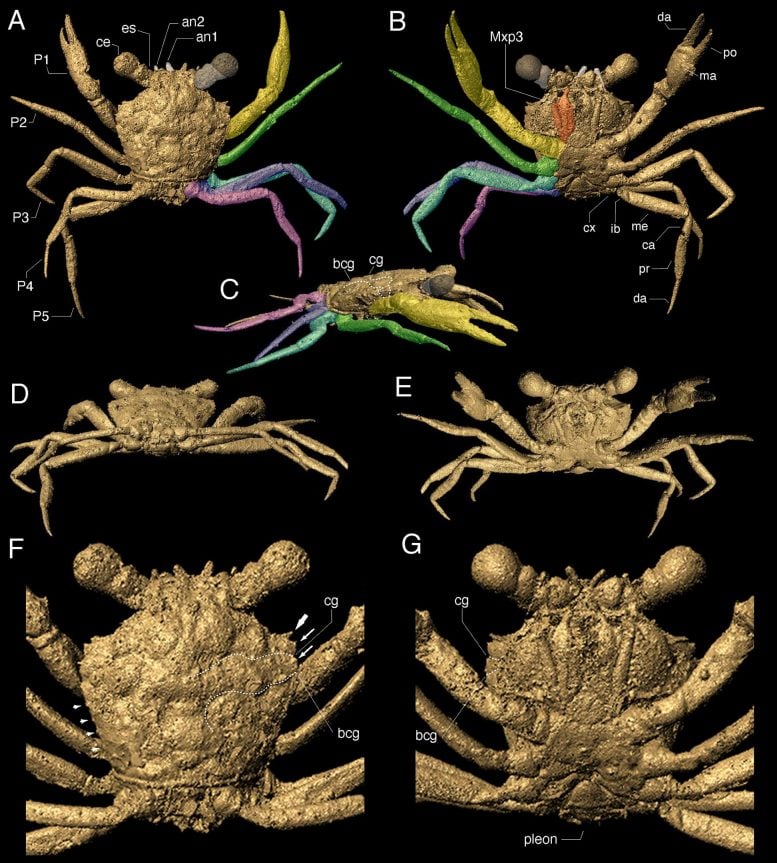

3D mesh of C. athanata Luque gen. et sp. nov. holotype LYAM-9. (A to E) 3D mesh extracted from reconstructed micro-CT data in VGSTUDIO MAX, remeshed in MeshLab, and visualized using Autodesk Maya: (A) dorsal, (B) ventral, (C) right lateral, (D) oblique postero-dorsal, (E) oblique antero-ventral views, showing the claws of equal size and four pairs of slender legs similar in shape and size, with P5 slightly smaller than the other legs. (F and G) Details of the dorsal (F) and ventral (G) carapace, showing details of the large eyes and orbits, small antennae, and a small, acute outer orbital spine [(F) thick arrow], two small anterolateral spines (F, thin arrows), a posterolateral margin bearing at least four small and equidistant tubercles (F, small arrows), straight posterior margin, slender coxae of the pereopods, a typical heterotreme eubrachyuran sternum (G), and a reduced and folded pleon with the first pleonites dorsally exposed. Left fifth pereopod digitally reattached. bcg, branchiocardiac groove; ca, carpus; cg, cervical groove; cx, coxa; da, dactylus; ib, ischiobasis; ma, manus or palm of claw; P1, claws or chelipeds; P2 to P5, pereopods or walking legs 2 to 5; po, pollex or fixed finger cheliped propodus; pr, propodus. Credit: Images and figure by Elizabeth Clark and Javier Luque. Used in journal.

The team, using micro-CT scans, was able to see in clear detail delicate tissues like the crab’s antennae, legs, and mouthparts lined with fine hairs, large compound eyes, and even its gills. Not even a single hair was missing, they said.

The study was a collaboration between Harvard and the China University of Geosciences, and included authors from 10 institutions including (function(d, s, id){

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = "https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.6";

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

Read original article here