Life reconstruction of Taytalura in its natural habitat with the extinct conifer Rhexoxylon in Ischigualasto (Argentina) during the Late Triassic, hiding from the primitive dinosaur Eodromaeus (in the background) inside the skull of a mammalian ancestor. Credit: Original artwork created by scientific illustrator Jorge Blanco

International team of researchers describe a new fossil species representing the ancient forerunner of most modern reptiles.

Lizards and snakes are a key component of most terrestrial ecosystems on earth today. Along with the charismatic tuatara of New Zealand (a “living fossil” represented by a single living species), squamates (all lizards and snakes) make up the Lepidosauria—the largest group of terrestrial vertebrates in the planet today with approximately 11,000 species, and by far the largest modern group of reptiles. Both squamates and tuataras have an extremely long evolutionary history. Their lineages are older than dinosaurs having originated and diverged from each other at some point around 260 million years ago. However, the early phase of lepidosaur evolution 260-150 million years ago, is marked by very fragmented fossils that do not provide much useful data to understand their early evolution, leaving the origins of this vastly diverse group of animals embedded in mystery for decades.

In a study published today (August 25, 2021) in Nature an international team of researchers describe a new species that represents the most primitive member of lepidosaurs, Taytalura alcoberi, found in the Late

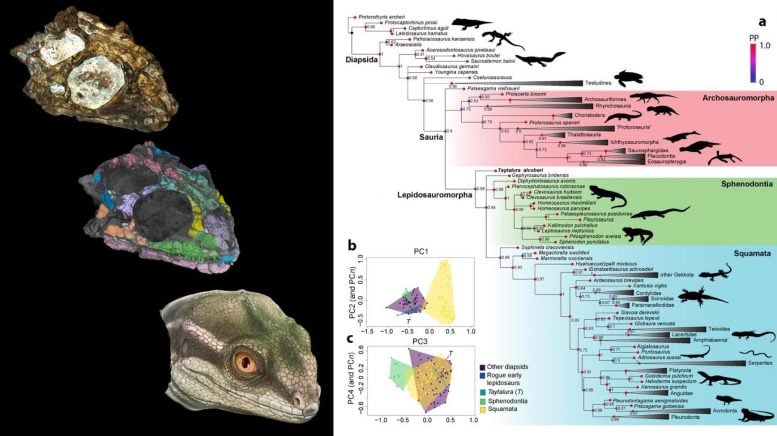

Reconstruction of the skull of Taytalura based on high-resolution CT scans (left) and its placement in the evolutionary tree of reptiles (right). Credit: (Left) Gabriela Sobral, Jorge Blanco, and Ricardo Martínez; (Right) Tiago Simões

Martínez and co-author Dr. Sebastián Apesteguía, Universidad Maimónides, Buenos Aires, Argentina, conducted high-resolution CT scans of Taytalura which provided confirmation that it was something related to ancient lizards. They then contacted co-author Dr. Tiago R. Simões, postdoctoral fellow in The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, to help identify and analyze the fossil. Simões specializes in studying these creatures and in 2018 published the largest existing dataset to understand the evolution of the major groups of reptiles (living and extinct) in Nature.

“I knew the age and locality of the fossil and could tell by examining some of its external features that it was closely related to lizards, but it looked more primitive than a true lizard and that is something quite special,” said Simões.

The researchers then contacted co-author Dr. Gabriela Sobral, Department of Palaeontology, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany, to process the CT scan data. Sobral, a specialist in processing CT data, created a mosaic of colors for each bone of the skull allowing the team to understand the fossil’s anatomy in high-detail resolution on a scale of only a few micrometers – about the same thickness as a human hair.

With Sobral’s data, Simões was able to apply a Bayesian evolutionary analysis to determine the proper placement of the fossil in the reptile dataset. Simões had recently applied the Bayesian method – which was adapted from methods originally developed in epidemiology to study how viruses like (function(d, s, id){

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = "https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.6";

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

Read original article here