The Whirlpool Galaxy, some 28 million light-years from Earth, looks to our telescopes like a cosmic hurricane littered with sparkling gemstones. Huge, lean arms spiral out from the centre of Whirlpool, also known as M51. Cradled within them are young stars flaring to life and old stars expanding, expiring and exploding.

In 2012 NASA’s Chandra Observatory, which sees the sky in X-rays, spotted a curious flicker coming from the galaxy. An X-ray source in one of Whirlpool’s arms switched off for about 2 hours, before suddenly flaring back to life. This isn’t particularly unusual for X-ray sources in the cosmos. Some flare, others periodically dim.

This particular source emanated from an “X-ray binary,” known as M51-ULS-1, which is actually two objects: Cosmic dance partners who have been two-stepping around each other for potentially billions of years. One of these objects is either a black hole or a neutron star and the other may be a large, very bright type of star known as a “blue supergiant.”

As astronomers looked a little more closely at the X-ray signal from the pair, they began to suspect the cause for the dimming may have been something we’ve never seen before: A world outside of the Milky Way, had briefly prevented X-rays from reaching our telescopes. The team have dubbed it an “extroplanet.”

A research team led by astronomer Rosanne Di Stefano, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, published details of their hypothesis in the journal Nature Astronomy on Oct. 25. Their study lays out evidence that the X-ray wink detected by Chandra was potentially caused by a planet, about the size of Saturn, passing in front of M51-ULS-1.

The extroplanet candidate currently goes by the name “M51-1” and is believed to orbit its host binary at about the same distance Uranus orbits our sun.

While many news sources have championed the detection as the “first planet discovered outside of the Milky Way,” there’s no way of confirming the find. At least, not for another few decades, when the proposed planet is supposed to make another transit of the binary. Di Stefano says the team modeled other objects that could potentially produce the dip in X-rays but came up short. Still, she stresses this is not a confirmed detection.

“We cannot claim that this is definitely a planet,” says Di Stefano, “but we do claim that the only model that fits all of the data … is the planet candidate model.”

While other astronomers are excited by the use of X-rays as a way of discovering distant worlds, they aren’t as convinced Di Stefano’s team has been able to rule out other objects such as large, failed stars known as brown dwarfs or smaller, cooler M stars.

“Either this is a completely unexpected exoplanet discovered almost immediately in a small amount of data or it’s something quite common or garden variety,” says Benjamin Pope, an astrophysicist studying exoplanets at the University of Queensland in Australia.

Hunting for hidden worlds

Astronomers have been probing the skies for decades, searching for planets outside of our solar system. The first confirmed detection of an exoplanet came in 1992 when two or more bodies were detected around the rapidly spinning neutron star PSR1257+12.

Prior to these first detections, humans had mostly imagined planets very similar to those we become familiar with in preschool. Rocky planets like the Earth and Mars, gas giants like Jupiter and smaller worlds, like Pluto, far from the sun. Since 1992, our ideas have proven to be extremely unimaginative.

Exoplanets are truly alien worlds with extremely strange features. There’s the planet where it rains iron, the mega Jupiter that orbits its home star in an egg-shaped orbit, a “naked” planet in the Neptune desert and a ton of super-Earths that seem to resemble home, just a little engorged. Dozens of strange, new worlds continue to be found by powerful planet-hunting telescopes each year.

But all of these worlds have, so far, been located within the Milky Way.

The Whirlpool Galaxy, M51, in X-ray and optical light.

NASA/CXC/SAO/R. DiStefano, et al.

It’s very likely (in fact, it’s practically certain) that planets exist outside of our galaxy — we just haven’t been able to detect them yet. Our closest galactic neighbour, Andromeda, is approximately 2.5 million light-years away. The farthest exoplanet we’ve found resides at just 28,000 light-years from Earth, according to the NASA Exoplanet Catalog.

Finding planets outside the solar system is not easy because less and less light makes its way across the universe to our telescopes. Astronomers rarely “see” an exoplanet directly. This is because the bright light from a star in nearby planetary systems usually obscures any planets that might orbit around it.

To “see” them, astronomers have to block out a star’s rays. Less than 2% of the exoplanets in NASA’s 4,538-strong catalog have been found by this method, known as “direct imaging.”

But one highly successful method, accounting for over 3,000 exoplanet detections, is known as the “transit” method. Astronomers point their telescopes at stars and then wait for periodic dips in their brightness. If these dips come with a regular cadence they can represent a planet, moving around the star and, from our view on Earth, periodically eclipsing its fiery host. It’s the same idea as a solar eclipse, when the moon passes directly in front of our sun and darkness descends over the Earth.

It’s this method that was critical to the discovery of M51-1. However, instead of detecting dips in visible light (a form of electromagnetic radiation), the team saw a dip in the X-rays (a different form of electromagnetic radiation). Because those X-rays were emanating from a relatively small region, Di Stefano says, a passing planet seems like it could block most or all of them.

M51-1

If M51-1 is a planet, Di Stefano’s team believe it may have had a tumultuous life.

It’s gravitationally bound to the X-ray binary, M51-ULS-1, which Di Stefano’s team posits consists of a black hole or neutron star orbiting a supergiant star. In the eons-old dance between the pair, the black hole or neutron star has been siphoning off mass from the supergiant. This mass, made of hot dust and gas, is constantly in motion around the black hole/neutron star in what’s known as an accretion disk. This hot disk gives off the X-rays detected by Chandra.

Regions of space around X-ray binaries are violent places and this disk doesn’t give off X-rays in a stable manner. Sometimes, the X-rays seem to switch off for hours, but pinning down the reason why is hard. “Within the very wide range of kinds of behaviors of these dynamic systems, it’s possible that some variation in the accretion rate or something like that could give rise to events like this,” says Duncan Galloway, an astrophysicist at Monash University studying neutron star binaries.

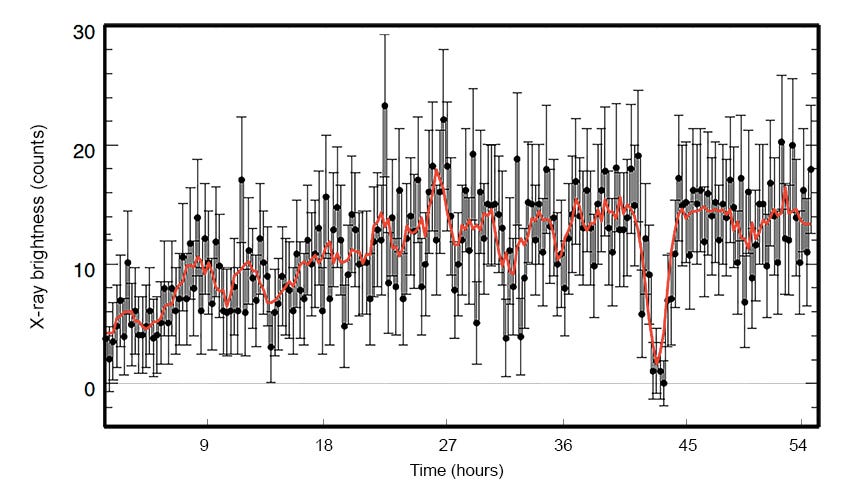

The dip in X-ray brightness is apparent on this graph, just prior to 45 hours — but was it caused by a planet?

NASA/CXC/SAO/R. DiStefano, et al.

One belief is the dimming could result from some of the hot gas and dust in the system obscuring the signal. Di Stefano says this is not the case, because gas and dust would provide a different signal. “As they pass in front of the x-ray source, some of the light from the source begins to interact with the outer regions of the cloud and this gives a distinctive spectral signature,” she notes.

Another possibility is the X-ray dimming was caused by different types of stars obscuring our view. One type, known as a brown dwarf, arises when a star fails to properly ignite. Another, an M dwarf, is a common type of star sometimes dubbed a “red dwarf.” But due to the age of the M51-ULS-1 system, Di Stefano’s team believe these objects would be much larger than the object they’ve detected.

Di Stefano’s team ran a load of models exploring various different scenarios for why the X-ray source switched off. In the end, she says, it was a Saturn-sized planet that seemed to fit what they were seeing best.

“The planet candidate model was the last one standing, so to speak,” says Di Stefano.

Pope is less convinced. “Personally, I wouldn’t bet that this is a planet,” he says. “In my view this is probably a stellar companion or something exotic happening in the disk.”

Trust The Process

This isn’t the first time NASA’s Chandra observatory has been swept up in a potential “extroplanet” find. Studying how radiation from distant stars is “bent” by gravity, a technique known as microlensing, astronomers at the University of Oklahoma believed they detected thousands of extragalactic planets back in 2018. Earlier studies have claimed to find evidence of extragalactic planets in the Andromeda galaxy.

Other astronomers were skeptical about these detections, too. The same skepticism has played out in the case of M51-1. And, importantly, that’s perfectly normal.

This is the scientific process in action. Di Stefano’s team have argued their case: M51-1 is an extragalactic planet. Now, there’s more work to do. Confirmation that M51-1 is planetary won’t be possible until it makes another transit of the X-ray binary in many decades time, but there are other ways for astronomers to vet their results.

Pope notes that if we found analogous systems in the Milky Way, we’d be able to follow up with optical telescopes and get a better understanding of what might be happening at these types of systems.

We know there must be planets outside of the Milky Way and so, eventually, humans will discover them. For Galloway, the study is exciting not because of what caused the X-ray binary to dip in brightness, but what happens next.

“The really exciting thing is there might be additional events in other data, so now we have a motivation where we can go and look for them,” he says.

Di Stefano feels the same way, hoping the publication will bring others into this type of research. She says the team is working hard, studying the skies for other X-ray binaries which may exhibit similar dimming.

“Ultimately,” she notes, “the best verification will be the discovery of more planets.”